2(3) 2008

|

|

|

ARCHITECTURE AND MODERN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES

ÌÅÆÄÓÍÀÐÎÄÍÛÉ ÝËÅÊÒÐÎÍÍÛÉ ÍÀÓ×ÍÎ-ÎÁÐÀÇÎÂÀÒÅËÜÍÛÉ ÆÓÐÍÀË ÏÎ ÍÀÓ×ÍÎ-ÒÅÕÍÈ×ÅÑÊÈÌ È Ó×ÅÁÍÎ-ÌÅÒÎÄÈ×ÅÑÊÈÌ ÀÑÏÅÊÒÀÌ ÑÎÂÐÅÌÅÍÍÎÃÎ ÀÐÕÈÒÅÊÒÓÐÍÎÃÎ ÎÁÐÀÇÎÂÀÍÈß È ÏÐÎÅÊÒÈÐÎÂÀÍÈß Ñ ÈÑÏÎËÜÇÎÂÀÍÈÅÌ ÂÈÄÅÎ È ÊÎÌÏÜÞÒÅÐÍÛÕ ÒÅÕÍÎËÎÃÈÉ

CROSSING INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ARCHITECTURE AND MEDIA. A pedagogic model for contemporaryeducation

ÏÅÐÅÑÅ×ÅÍÈÅ ÂÇÀÈÌÎÄÅÉÑÒÂÈÉ ÌÅÆÄÓ ÀÐÕÈÒÅÊÒÓÐÎÉ È ÑÐÅÄÀÌÈ. Ïåäàãîãè÷åñêàÿ ìîäåëü äëÿ ñîâðåìåííîãî îáðàçîâàíèÿ

Leandro Madrazo

ARC Enginyeria i Arquitectura La Salle, Universitat Ramon Llull, Barcelona

http://www.salle.url.edu/arc

The course Systems of Representation

Today, knowledge is no longer considered to be structured in separate disciplines. Inter-disciplinarity is the hallmark of contemporary culture. In this context, our role as educators is to provide students –also in architecture– with the cognitive skills that enable them to understand the contemporary world and to contribute to the construction of the trans-disciplinary knowledge that distinguishes our culture.

In the course Systems of Representation (www.salle.url.edu/sdr/info), we have created a pedagogic framework which embraces a variety of disciplines, basically: art and architectural theory, aesthetics, gestaltung, graphic design, visual communication, and computation (Madrazo, 2006). This multidisciplinary approach fosters a fruitful exchange between different areas of knowledge. The multiplicity of connections between subjects brings about a knowledge that transcends disciplinary boundaries.

Around each one of the six Systems of Representation –Text, Figure, Image, Object, Space, Light– a theoretical framework is built up with ‘theory bits’ taken from different disciplines which are put into relation. The relations, rather than the specific content, make up the theoretical framework of the course. Exercises are not meant to be practical applications of established theories. Topics brought up in the lectures are subsequently explored by students in the exercises, so that they can contribute with their works and reflections to the network of relationships.

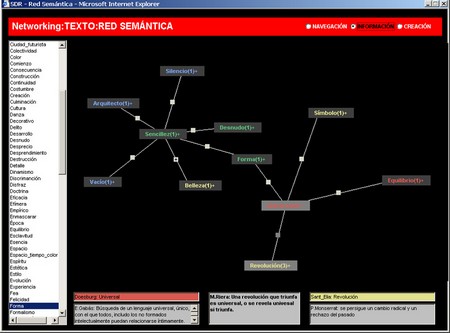

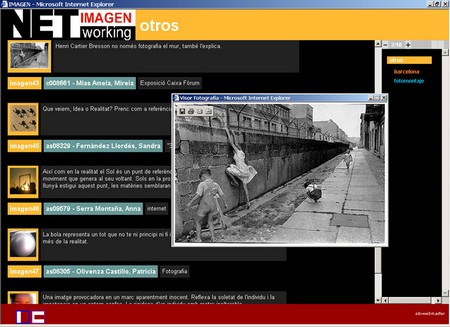

According to constructivist pedagogy, knowledge does not exist beforehand and, therefore, it cannot just be transmitted from teacher to student. Rather, knowledge is thought of to be a collaborative, social construction which emerges from the interaction between learners. In accordance with this philosophy of education, we have created web-based learning environments specifically for this course, in order to support the exchange of ideas among students and teachers, for example, to analyze architectural theory texts with conceptual maps constructed in collaboration (Fig. 1), or to elicit meaning from images stored in digital libraries (Fig. 2)

|

|

|

| Fig. 1. Web-based environment to construct concept maps in collaboration | Fig. 2. Web-based environment to collect and elicit meaning from images |

The course combines web-based learning spaces with traditional education (blended learning). Instead of replacing face-to-face contact with Internet, the web-based environments enhance the traditional classroom-based model with new learning spaces where the collective work of the class is visualized in a unique manner with the support of information technology, allowing students to collaboratively reflect upon the interrelationships between works and ideas.

The pedagogy of perception

As in the Vorkurs taught in the Bauhaus first by Itten and later by Albers and Moholy-Nagy (Borchardt-Hume, 2006), one of the goals of the course Systems of Representation is to unfold the capacity of a student to think visually, through the conceptual and technological instruments which are specific of our time.

One of the early pedagogic objectives of the Bauhaus pedagogy was to come up with new teaching methods to respond to the needs of the industrial society which emerged in the nineteenth century (Wick, 2000). Today’s pedagogic models have to respond to the needs of a society immersed in a continuous process transformation. However, we are no longer living in an industrial society but in a knowledge and information society. The contemporary world is not so much conformed by objects massively produced by industry, but mostly by the ubiquitous images produced by media: television, cinema, video, advertisement, Internet, mobile telephones, and television displays. Our reality, as Debray has written, is a mediavision of the world at a planetary scale (Debray, 1992).

In much the same way as the modern metropolis determined the development of new cognitive skills, the media (television, radio, and press) contributed to enhance and shape our cognitive capacities, as McLuhan (1994) had proclaimed. In our time, Internet, along with mobile phones and digital players, are decisively contributing to shape not only our cognitive skills –particularly those of the young people, who are able to respond to a large amount of information characterized by the velocity and fragmentation of the visual stimuli, as well as by the simultaneity and immediacy of the messages– but are also transforming the world into a mediascape.

Therefore, our pedagogic systems need to constantly renew the links with the rapidly transforming world which is emerging from the interaction between media and technology. We are subjected to a continuous flux of information which is mostly visual. As consumers we are permanently exposed to the enticing images created by advertisement. Images which are particularly attractive because of their aesthetic qualities, the narratives and stories they convey, and the density of information they embody.

In the themes Text and Image of the course Systems of Representation, architecture students are able to acquire and develop the capacities that enable them to understand our mediated world. Photography and film were the most advanced techniques that progressive teachers such as Moholy-Nagy could use to instill their students with the spirit of the industrial society and to forge in them the necessary cognitive skills to understand the world they lived in (Moholy-Nagy, 1987). In our course, we use digital tools as instruments for creating and communicating, and also to support collaborative processes of knowledge construction, using words and images as knowledge “building blocks”.

Modern art and advertisement

With the artistic avant-gardes of the beginning of the twentieth century, both the notion of art as an autonomous discipline and the vision of the artist as an individual especially endowed to perceive and reproduce beauty disappeared. Furthermore, the boundaries that had kept art and life apart along with the distinction between artistic creation and industrial production began to dissolve. The modern artist strove for constructing a new world, rather than representing the existing one. Russian constructivists were willing to contribute to the creation of the new culture arising from the revolution; they were not only artists but active propagandists working for the ideals of a new society. In many of the graphic works by Rodchenko or Lissitzky it is difficult to distinguish between the work of art and the propaganda leaflet. In those works, the limits between art, graphic design and advertisement were blurred.

The industrial society which emerged in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century needed new graphic languages (typography, graphic design) and new forms of communication (photography, photomontage, advertisement). It became necessary to come up with visual languages which were not necessarily constrained to the artistic realm, but which could be applied to all kinds of visual production. Images were assessed not just for their “beauty” but mostly for their effectiveness in the creation of meanings and the transmission of messages.

The work of the historic avant-garde movements of the beginning of the twentieth century is a necessary referent for the pedagogic approach adopted in this course. Our goal, however, is not so much to emulate the works produced in that period, as to continue developing further their premises in the context of contemporary culture.

Interactions and hybridizations between art, architecture and media

In our time, the convergence of art and advertising has reached a point in which it is no longer possible to distinguish between both: advertising seeks inspiration in the works of artists, while these, in their works, reproduce a view of the world which has been forged in and by the media. On the other hand, artists –in much the same way as politicians or entrepreneurs– employ advertisement techniques to arrive to the public. All of them know that they need to have a presence in the media (e.g. to have an image) to exist (e.g. succeed) in the real world.

As Baudrillard contended, today the totality of the world (art, politics, economy) has been “aestheticized” (Baudrillard, 1990), that is to say, it has become an artistic creation originated and reproduced in and through the media. As a result art has disappeared. Creation now takes place not only within the privileged world of art, but in the crossing interactions between distinct realms. In this situation, the interrelationships between architecture and advertising, between advertising and media, bring about fruitful exchanges of ideas resulting in hybrid productions. Projects such as a commercial campaign for Prada might start in one realm (fashion, advertisement) and end up materialized in another one (architecture) as an object which is both a marketable product and cutting edge architecture (shops designed by Koolhaas and Herzog and de Meuron).

This hybridization between art, advertising and media has been deliberately undertaken by some contemporary architecture. The architect Rem Koolhaas, together with the graphic designer Bruce Mau, compiled the work of his architectural office in the book S, M, L, XL (Koolhaas and Mau, 1995). The title of the book already suggests that their architecture is a consumer’s product. Its content is a compendium of disparate images and fragmented texts which altogether not only represent but reproduce the world we live in: a world which consists of visual impressions, of bits of information, which are constantly bombarding us; a world as evanescent as Koolhaas’ buildings tried to be

System of Representation Text: interpretation and translation

The lectures in the theme Text encompass linguistics (syntax, structures), semiotics (sign, reference), graphic design (typography, poster design), interactive media (interface design, interactivity), advertisement (television spots, banners) and architectural theory (aesthetic principles of modern architecture). The exercise consists of analyzing manifestoes of modern architecture, and to translate their content into a multimedia production, to be published in the Web.

The exercise is carried out along several lines in parallel. First, the content of the manifesto is summarized in three concepts, which are submitted to a web-based learning environment to create a common critical vocabulary. After analyzing the vocabulary (e.g. comparing definitions of the same concept in different manifestoes), students create relations between concepts which are represented in a concept map which is built in collaboration. The subsequent exploration of the map becomes a source of new knowledge. This sequence of tasks ends with a written text explaining the relationships of a selected portion of the concept map. The final text –an elicitation of ideas contained in the concept map– is not meant to represent a mere “coexistence of meanings” but to be a “passage, a traversal”, as Barthes (1996) had put it; not the answer to an interpretation, but an “explosion”, a “dissemination” of meanings, derived from the map.

Simultaneously to the collaborative construction of the concept map, each student working individually translates the content of one manifesto into a multimedia presentation. To do that, he or she needs to first understand the text, learn about the author’s works and thoughts, and place the issues discussed by the author of the manifesto in the appropriate historical context. Moreover, by analyzing the text students realize that many of the matters which concerned modern architects –form, material, technique, culture– are also an issue for contemporary architecture. Then translating the manifesto becomes an opportunity to establish links between the ideas that inspired modern architecture, and the contemporary architectural discourse.

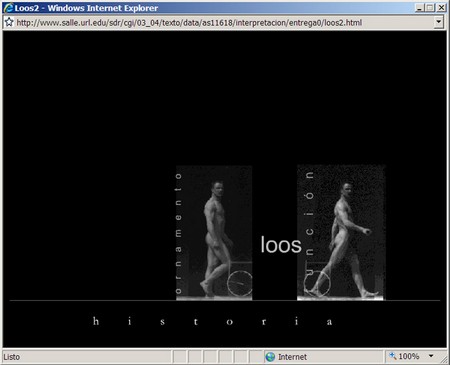

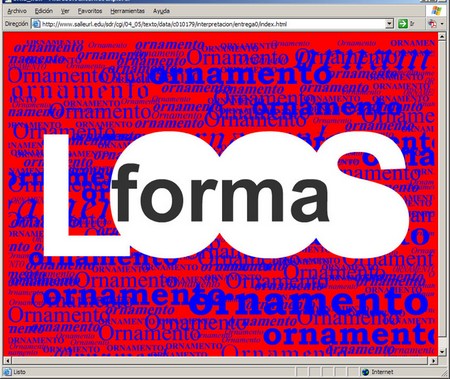

The goal of the multimedia presentation is to communicate the main ideas of the manifesto –as they have been interpreted by the student– in an effective manner. To achieve this goal, it might be appropriate to turn to narrative structures as those used in television spots. The aesthetic of the multimedia presentation must also be in accordance with the content of the manifesto (Helfand, 2001). For example, in the multimedia translation of “Ornament and Crime” (Fig. 3) an early motion picture is used to evoke the period when Loos wrote the text. In the case of an interactive presentation meaning is elicited as the user interacts with the multimedia production. For instance, in the exercise in Fig. 4, the cursor is represented by the word LOOS. As the user moves the cursor on the screen, ornament is being removed to make form appear: it is Adolf Loos who through his writings and buildings gets rid of the superfluous decoration.

|

|

| Fig. 3. An interactive presentation of the text “Ornament and Crime”, by Ricardo M. del Val, 2003/04 | Fig. 4. An interactive presentation of the text “Ornament and Crime”, by Agustí Canadell, 2004/05 |

Altogether, the intertwining of architectural theory, narrative structures, graphic design, advertisement and interactive media, makes the exercise of translating an architectural manifesto in a multimedia production an example of interdisciplinary education. It also points out ways in which visual digital media can gain a theoretical status which is still considered exclusive of printed works (Bolter 2003).

Students have reacted positively to this pedagogic experience. Most of them consider that translating the manifesto to a multimedia format motivates them to understand their meaning, and find the task of communicating architectural ideas with texts, images, sounds and motion, a challenging one. On the other hand, some of them still see authoring multimedia production tools as a barrier that they need to overcome to be able to communicate their ideas effectively.

The contemporary culture of the image

The ubiquity and promiscuity of images characterizes our existence. We are permanently surrounded by images that mediate between us and the real world. After the invention of photography in the nineteenth century any person with a camera became a producer of images. Then the production of images stopped being a privilege of a few people. Today, with digital photography not only the possibility for anybody to produce images has increased even more, but also the opportunity of distributing them through the electronic networks (Internet, telephone) has reached unknown limits. The presence of images in all kinds of support (prints; billboards and screens; television, computer and mobile telephone displays), generated by “imagining technology” (Maynard, 1997) has transformed the world into a mediascape consisting of images which not only represent an objective reality to make it intelligible, but which are reality.

This omnipresence of the image has led to some authors to consider our culture as being a fundamentally visual one. According to Debray (1992), during the decades from 1960 to 1980, western culture ceased to be based on the written sign (logosphere) to become a visual culture, based on images (videosphere). The emergent culture of the image demands individuals to have new cognitive skills, different to those acquired in a world dominated by the written word. This predominance of the image, however, does not necessarily entail the disappearance of the text superseded by the image. Text and image cannot exist without each other. As a matter of fact, there have always been intricate links between the written and the visual culture which new media has only made even more complex (Hocks and Kendrick, 2003). The challenge for contemporary culture, therefore, is not so much to replace a culture based on the written word by one based on the image, but to redefine the relationships between them.

The pedagogy of the image

The primacy of images in contemporary culture calls for a revision of our pedagogic methods and objectives. Images are not born within the limits of a particular domain, but are the result of continuous processes of “re-mediation” (Bolter and Grusin, 1999), that is to say, the reciprocal influence among the different media (television, cinema, Internet). As Traub (1997) has stated: “We can no longer speak about photography as art or design or communication. It is not a question of film vs. video or text vs. image. We can only conceive that the postmodern image is an image of multimedia which reflects the spirit of our time without hierarchies and authoritative voices”. In this context, new theoretical frameworks that transcend established disciplinary limits are necessary to understand the complexity of images and to learn to think and create with them. The emerging area of Visual Studies (Mirzoeff, 1999) aims at creating such a framework, by considering images with independence of technique (painting, photography, and video), function (art, communication) or media (television, Internet). As Rodowick (2001) has written: “Visual studies holds together as a discipline through a consensus based on recognizing commonalities among ‘visual’ media –painting, sculpture, photography, cinema, video and new media– and the critical theories that accompany them.”

Photomontage, city, advertisement

By the end of the nineteenth century, the appearance of metropolis such as Paris or Berlin brought about a new sensibility and a new individual: the metropolitan citizen. Simmel (2002) argued then that in the metropolis people had to develop new skills to be able to respond to the continuous and varied stimuli: “Thus the metropolitan type –which naturally takes on a thousand individual modifications –creates a protective organ for itself against the profound disruption with which the fluctuations and discontinuities of the external milieu threaten it. Instead of reacting emotionally, the metropolitan type reacts primarily in a rational manner, thus creating a mental predominance through the intensification of consciousness, which in turn is caused by it.” This “intensification of consciousness”, as Simmel put it, would explain the intellectual behavior of the urban citizen as opposed to the emotional conduct of the rural inhabitant. Unlike the rural inhabitant who could rely on inherited patterns of cognition, the metropolitan type had to develop other cognitive capacities to adapt to a more dynamic environment.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, photographs, photomontages and films became the appropriate techniques to represent not only the modern metropolis, but also the mind of the modern individual. The photomontage from Paul Citroen, Metropolis, 1923, conveys the idea of a city which cannot be apprehended as a totality (Ades, 1996). This photomontage does not only represent the city as an object, but rather it reproduces the experience of the modern citizen who perceives the metropolis as an unstable configuration of fragments, a patchwork without limits and without form.

Photomontage was a favorite technique for the avant-garde artists –particularly Dadaists, Constructivists and Surrealists– because it allowed them to fragment reality –represented by photographs– and recompose it in new ways. With photomontages those artists were able to create a new reality and, at the same time, to keep a link with the objective world because of the photographic image.

In our time, however, the link between image and reality has dissolved. As Baudrillard (1996) has persuasively argued: “Abstraction today is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.” After the world has been completely aestheticized, the relationship between image and city has also changed. Images do not represent cities, rather cities have become images. During the last decades, cities have become marketing products, objects of consumption for the mass tourism. Cities all over the world have become more aware of the importance of having a distinctive identity. Therefore, they are striving to become a “brand” so that they can become a node in the network of global cities where the fluxes of assets and people circulate. This affluence of “city images”, distributed through the media, has made it possible to experience a city without having actually visited it (Coates 2003). The experience of today’s city does no longer takes place in the actual territory, but in a simulacrum: the image of what we think the city was or ought to have been.

System of Representation Image: understanding and representing the urban environment with images

In the theme Image, the network of ‘theory bits’ encompasses different realms: photography, painting, advertisement and digital media. In line with the Visual Studies approach, lectures take into consideration the philosophical, aesthetic, technological and cultural dimensions of images.

The sequence of exercises is the following: 1. Perception of the image in the mediascape: selection and interpretation of images taken from any media (print, television, Internet). Images are submitted to the web-based environment to create a digital library collaboratively 2. Perception of the image in the urbanscape: photographing the urban environment. Photographs submitted to the digital library are then classified and commented 3. Associations between images: images from the urban and mediascape are organized in groups using the web-based environment 4. Using the images collected in the library and the associations found among them, each student makes a photomontage which conveys a personal view of the contemporary city.

Constructivist artists exploited the capacity of photomontages as effective means for propaganda. They began to realize that messages built with photographs reached people more directly that those based on texts. Later, artists like Heartfield used photomontages as an instrument for political critique. Since then, the photomontage has become an established communication technique that we can see in the media every day. As advertising agencies know very well, the satire and humor which are inherent to photomontage are very effective means of grasping the beholder’s attention and of communicating an idea in a direct manner.

In order to effectively communicate a personal view of the contemporary city with photomontage, students need to understand the mechanisms of this communication technique. At the outset, it is necessary to be aware of the multiplicity of meanings and codes that the images intervening in the composition convey. Each image carries its own connotations. For instance, in Fig. 5, we can recognize the well-known scream of Munch in the contorted figure. In the photomontage, the “scream” represents the fear of the citizen in front of a city –represented by the Casa Batlló by Gaudí– transformed in the house of horrors of an adventure park to satisfy the demands of mass tourism. In order to unfold the meaning of the photomontage the beholder needs to have knowledge of the meanings of the images which this encompasses as well as the interactions between them.

|

|

|

Fig. 5. The scream of the citizen in front of the city transformed in a theme park. Photomontage by Iranzu Santamaría, course 2004/05. |

Conclusions

With the pedagogic strategy we have adopted, content and media, individual expression and collaborative work, become intertwined. An interactive presentation of a text on architectural theory becomes an opportunity to discuss about linguistic structures, semiotics, graphic design, net-art and advertisement. Around a photomontage of the city, television spots and photography, painting and film, urban theory and space perception, are put into relation. This interweaving between architectural theory and media, urban environment and photography, interface design and advertisement, bring about not only a hybridization of the different media but most important, give rise to a contemporary view of architectural subject-matters, as fluid and contingent as the dynamic relationships that produces them.

Acknowledgments

The web-based learning environment used in the course Systems of Representation has been created by the research group ARC Enginyeria i Arquitectura La Salle (www.salle.url.edu/arc). Architects Eduardo Hernández and Mario Hernández, and fine arts graduate Marta Sabat have collaborated in the teaching of the courses. We would like to thank the students of the second and third year of Arquitectura La Salle for their participation in this pedagogic experience and for their good work.

References

Ades, D.: 1996, Photomontage, Thames and Hudson Ltd., London.

Barthes, R.: 1996, From Work to Text, in B. Wallis (ed.) Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, The New Museum of Contemporary Art and David R. Godine Publisher Inc., New York and Boston.

Baudrillard, J.: 1996, The Precession of Simulacra, in B. Wallis (ed.) Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, The New Museum of Contemporary Art and David R. Godine Publisher Inc., New York and Boston, pp. 253-281.

Baudrillard, J.: 1990, Towards the Vanishing Point of Art, in F. Rötzer and S. Rogenhofer (eds), Kunst machen? Gesprache und Essays, Boer, Munich.

Bolter, J. D. and Grusin, R.: 1999, Remediation: understanding new media, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Bolter, J. D.: 2003, Critical Theory and the Challenge of New Media, in M. E. Hocks and M. R. Kendrick (eds): Eloquent Images. Word and Image in the Age of New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Borchardt-Hume, A.: 2006, Two Bauhaus Stories, in A. Borchardt-Hume (ed.), Albers and Moholy-Nagy. From the Bauhaus to the New World, Tate Publishing, London.

Coates, N.: 2003, Guide to ecstacity, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Debray, R.: 1992, Vie et mort de l’image: une histoire du regard en Occident, Gallimard, Paris.

Helfand, J.: 2001, Screen. Essays on Graphic Design, New Media, and Visual Culture, Princeton Architectural Press, New York.

Hocks, M. E. and Kendrick, M. R. (eds): 2003, Eloquent Images. Word and Image in the Age of New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge

Koolhaas, R. and Mau, B.: 1995, Small, medium, large, extra-large, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam.

Madrazo, L.: 2006, Systems of representation: a pedagogical model for design education in the information age, Digital Creativity, 17 (2), pp. 73-90.

McLuhan, M.: 1994, Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Maynard, P.: 1997, The Engine of Visualization. Thinking through Photography, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

Mirzoeff, N.: 1999, An Introduction to Visual Culture, Routledge, New York.

Moholy-Nagy, L.: 1987, Painting, Photography, Film, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Rodowick, D. N.: 2001, Reading the Figural. Or, Philosophy after the New Media. Duke University Press, Durham & London.

Simmel, G.: 2002, The Metropolis and Mental Life, in G. Bridge and S. Watson (eds), The Blackwell City Reader, Blackwell Publishing, Malden.

Traub, C.: 1997, Statement, in G. Jäger and G. Wessing (eds), Über Moholy-Nagy, Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld.

Wick, R.: 2000, Teaching at the Bauhaus, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern.